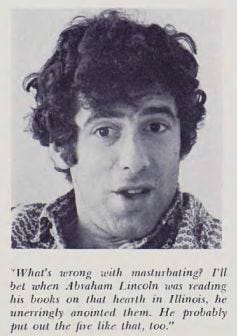

A love letter to Elliott Gould 1969 - 1974

Andrew Key explores his cinephilic obsession with the legendary actor who defined an era of American cinema with his charming and highly sexualised hunks

What has happened to cinephilia during the pandemic? Cinematic desire has always changed with the film industry and the technologies available to it. There are many kinds of desire at work when we watch a film: desire for the actors, for their lives and for their bodies, but also desire for the fantasy world of the films, or even desire for the cinema itself, for its apparatus and space. It used to be the case that you went to the cinema to sit in a dark room, surrounded by people but still alone, and stare in silence at the face of an extremely beautiful person blown up to a preposterous size for a few hours: an erotics of devotion.

Going to the cinema and watching a film has been a conduit for sexual fixation since the Lumière Brothers, and you can read Samuel R. Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue for a thorough discussion of cinemas used for public sex. In a talk I saw him give once, the film historian David Thomson made an overblown statement about how the cinema has made everyone bisexual: watching movies so effectively blurs the line between wanting to be someone and just plain wanting them that none of us can really figure it out anymore, regardless of our gender or the gender of the person we’re staring at, and it will take centuries for us to understand the full extent of the impact that cinema has had on human sexuality. I’ve skim-read my Freud so I already knew that everyone was already bisexual before the advent of the cinema, but Thomson’s idea has really stuck with me. What do the films we watch do to us and our desire, and does it matter how we watch them?

Now that cinemas have (for the most part) been closed for over a year, and now that everyone streams or torrents everything in the comfort of their own home anyway, a new kind of cinephilia has surely arrived. This cinephilic drive will manifest itself differently for others than it does for me, but I’ve always had a slightly fetishistic penchant towards being a completionist: if I get into something, I have an urge—hard to control or resist—to consume all of it; I gorge myself compulsively on every book by a particular writer, every film by a director, everything starring a certain actor, until there isn’t anything by them left and then I feel disillusioned and overly-sated—a very particular and weird kind of post-coital melancholy. This is even easier than it used to be: nowadays I can sit in bed and download—legally or illegally—pretty much everything I want to watch; no matter how obscure it is, someone will have put it out there on the internet. And then I can watch it over and over again, and I can screenshot the moments that cause a particular frisson, and then I can post them on Twitter to publicise my fixation. (You can ask my therapist what needs I think I’m meeting with this behaviour, and if you’re about to prudishly sneer at me for being a perverse viewer then I suggest you really examine your own viewing habits first.)

I’ve had a few different phases throughout the last year or so, getting way too into a number of different objects of desire, but most recently my fixation has been latched firmly and intensely onto the film career of Elliott Gould between 1969 and 1974. My interest in his career evaporates immediately after 1974, and I haven’t bothered with the few bit-parts he had before 1969, but otherwise I’ve sought out and sat through all of his work from this period.

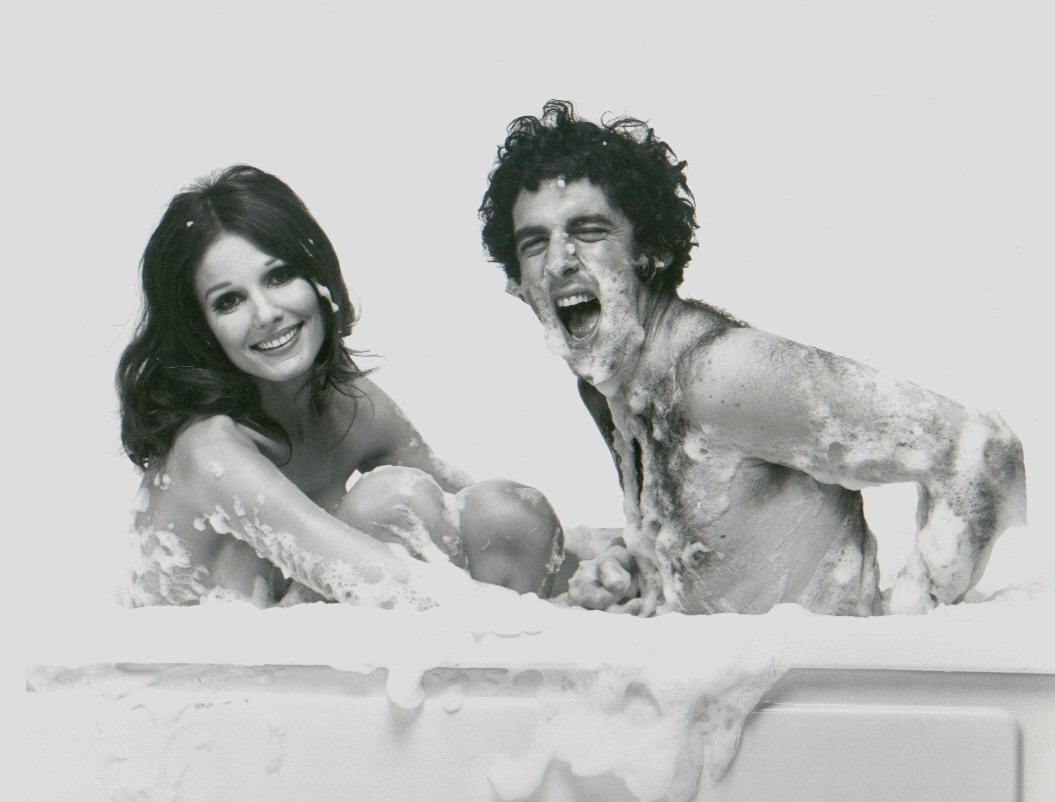

If you watch all twelve feature films from the first five years of Elliott Gould’s cinematic career, starting with Paul Marzusky’s Bob & Alice & Ted & Carol (1969) and ending with Robert Altman’s California Split (1974)—as I have just spent the last week or so doing, going out of my way to track down the more obscure films in shitty low-quality VHS rips—you will see a lot of flesh. Most of the films from this period of Elliott Gould’s career are sex comedies and most of them give him—as well as the various women he is seducing or being seduced by in these films—at least one opportunity to disrobe. He often puts on a pair of pyjamas, sky blue or salmon pink, which he wears while arguing with someone in bed before either having or failing to have sex. (Pyjamas perform a particular function in the sex comedy genre that I haven’t figured out—something to do with foreplay and frustration.) The image has stayed in my mind of Elliott Gould in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, wearing his blue PJs, running on the spot to burn off some excess energy after getting stoned, with the bottom button on his pyjama jacket undone so a triangle of hair and skin is tantalisingly visible, his lower stomach, from his waistband to his navel. In some of his films from this period (especially Stuart Rosenberg’s Move, a subpar and vaguely surrealist comedy about the difficulties of finding a reliable removals service in New York City, from 1970) Elliott Gould gets undressed about once every ten minutes—maybe even more than that. Sometimes he just strips down to his underwear, which is usually an unflattering pair of large white briefs, as was the style at the time, but sometimes he takes everything off, and slips under some bedsheets or into a bath before the camera is permitted any suggestive glimpses of what’s going on below his waist—again, the strange chasteness demanded by the generic conventions of the sex comedy: plenty of bare breasts on display, but little else.

Elliott Gould is a tall guy, somewhere over six foot, and he’s also a big man. If Elliott Gould had been a star in the fifties (not that he’d have been allowed—he’s too excessive in his performances, he’s too neurotic, in other words too Jewish for 1950s Hollywood), he’d have fallen into the masculine category of the beefcake, and would possibly have been compared to someone like Rock Hudson—but Rock Hudson’s career was built on the perfect almost-hairlessness of his enormous torso, his non-threatening hygiene, whereas Elliott Gould is a hirsute man, with a lot of back hair, and as often as not sporting a Zapata moustache. There’s an essay from the early 90s called “Rock Hudson’s Body”, written by the art historian Richard Meyer, which describes the ways that the constructed image of Rock Hudson as a sexually-passive gentle giant effectively sanitised and made acceptable the erotic charge that viewers (both female and male) got from looking at his preposterously large body (deliberately shot to seem to exceed the frame) in his movies and publicity photos, all in aid of the production of a clean and pure heterosexuality untainted by the messiness of any actual fucking. The irony of this, as Meyer points out, is that this sanitary straightness was concocted by a publicity machine largely consisting of gay men (Rock Hudson’s manager and agent, Henry Wilson, in particular), and the very site of this desirable cleanliness was the body of man who also preferred sleeping with men. (The open secret of Rock Hudson’s own sexuality was covered up in his heyday by a three-year lavender marriage to Phyllis Gates, which worked well enough until he went public with his AIDS diagnosis in the 80s.) Rock Hudson’s body is a useful demonstration of how queer male erotic fantasies can saturate popular culture and our collective imaginations, for men and women, straight or not, even when they aren’t ever made explicit—or, in the case of Rock, are explicitly denied.

But Elliott Gould 1969–1974 is not really like Rock Hudson, a passive hunk onto which the viewer’s desire is safely projected and contained; a man who is allowed a chaste on-screen kiss now and then, but who is more often than not the pursued rather than the pursuer. Rock Hudson does not fuck, but Elliott Gould 1969–1974 certainly fucks. At least, for the most part he does; at least, sex is a concern for him, in a way that it never was allowed to be for Rock. In his films, Elliott Gould 1969–1974 is almost always a highly sexualised figure: his career fully takes off in years of cultural promiscuity and a lot of his movies from this time are about adultery: films about the bourgeoisie dabbling with wife swapping, or neurotics getting off the couch and into bed. Fresh from his divorce from Barbra Streisand, Elliott Gould 1969–1974 either has a lot of sex in his films or he is surrounded by beautiful women who want to have sex with him despite his refusals. In 1970, annus mirabilis, he was the lead in four films, and was one of the biggest names in the movies: this fame is itself a kind of virility. Up until he worked with Ingmar Bergman on The Touch in 1971, Elliott Gould spends his films sleeping with either his wife or girlfriend or other people’s wives and girlfriends. Then his career is somehow ruined by Bergman and he gets too big for his boots perhaps: he hits a wall by acting erratically during the production of A Glimpse of Tiger (eventually made as What’s Up, Doc? by Peter Bogdanovich, starring none other than Barbra Streisand in the part Gould was supposed to play), and he goes away and has psychoanalysis for a couple of years, before returning to the screen in a more chaste and erotically detached mode.

At this point in his career, even if he’s pursued or has the opportunity to fool around with someone, no strings attached, Elliott Gould 1969–1974 generally turns them down. It so happens that these denials of his former sexual excesses usually take place in his better films, especially two of those he made with Robert Altman: The Long Goodbye, in which he lives next door to a bunch of young women with a taste for doing naked yoga on their balconies, where he’s just a respectful and good neighbour to them, a guy who buys them brownie mix and doesn’t bat an eyelid at all that exposed and tanned skin; and California Split, in which he lives with two sex workers with hearts of gold, with whom he pals around and is mothered by—but the relationship seems not to have even a remote tang of the erotic, and he prefers spending his time involved in an elaborate seduction of George Segal. These films are more aggressively homosocial than his earlier work, with the exceptions of M*A*S*H and Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice: they are transparently about men wanting to hang out with each other, to the sometimes intentional and sometimes unintentional exclusion of women. In psychoanalysis a no is often a yes. Elliott Gould 1969–1974 often is saying no to the women and yes to the men. This might be to do with Robert Altman’s misogyny as much as it’s anything to do with Elliott Gould 1969–1974 himself, but it’s also—for better or worse—part of where my fantasies take over: when I watch California Split, I don’t want to be Elliott Gould. I want to be George Segal, inundated and dazzled by Elliott Gould’s charisma and charm and energy and humour. I want to go to the bar with him and then for us to wind up back at his apartment.

Elliott Gould 1969–1974 is straight. That seems pretty obvious, and also has to be more or less taken for granted, since there was effectively no scope for explicitly acknowledged same-sex male desire in the masculinist just-guys-being-dudes American cinema of the early 1970s; a period of filmmaking which seems particularly concerned with men trying to figure out what kind of relationships they can have with each other in the disillusioned and cynical years after the utopian impulses of the 1960s had hardened and crumbled. Despite being a part of “New Hollywood” (and its turn away from the figure of the star and the studio system and towards the director), Elliott Gould 1969–1974 is a star in the classic sense of the word, and as such always seems to play himself in these movies. It doesn’t matter what film you watch, you’re watching Elliott Gould. He said as much in interviews; there’s no method acting here, he just turns up to set and is himself. His characters are straight and they just like hanging out with other guys; sports are important for him, particularly basketball—the perpetually sanctioned realm of expressive homosociality.

Personally, I don’t care about sports and I’ve got no illusions that Elliott Gould 1969–1974 and I are going to grab a few beers and then maybe, if things go well, we’ll end up back at his apartment and start fooling around. But surely this is what cinema is for, and what it’s always been for: fantasy. It’s about the construction of ego-ideals (I want to be Elliott Gould 1969–1974) and about allowing ourselves to be surprised by our desire, and then perhaps to understand it better (I want to fuck or be fucked by Elliott Gould 1969–1974). Films are not a good guide to life, or to human nature and behaviour, or to the questions of what we should do and who we should be while we do it, but nevertheless that’s what we use them for. In a time when our access to other people is scarce and fraught with risk and uncertainty, the cinephilic fixation gives us something that we don’t get in many other places—a way of trying to answer those crucial questions: what is it that I want? And who is it that I want it from?

PS A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF ELLIOTT GOULD FILMS 1969–1974

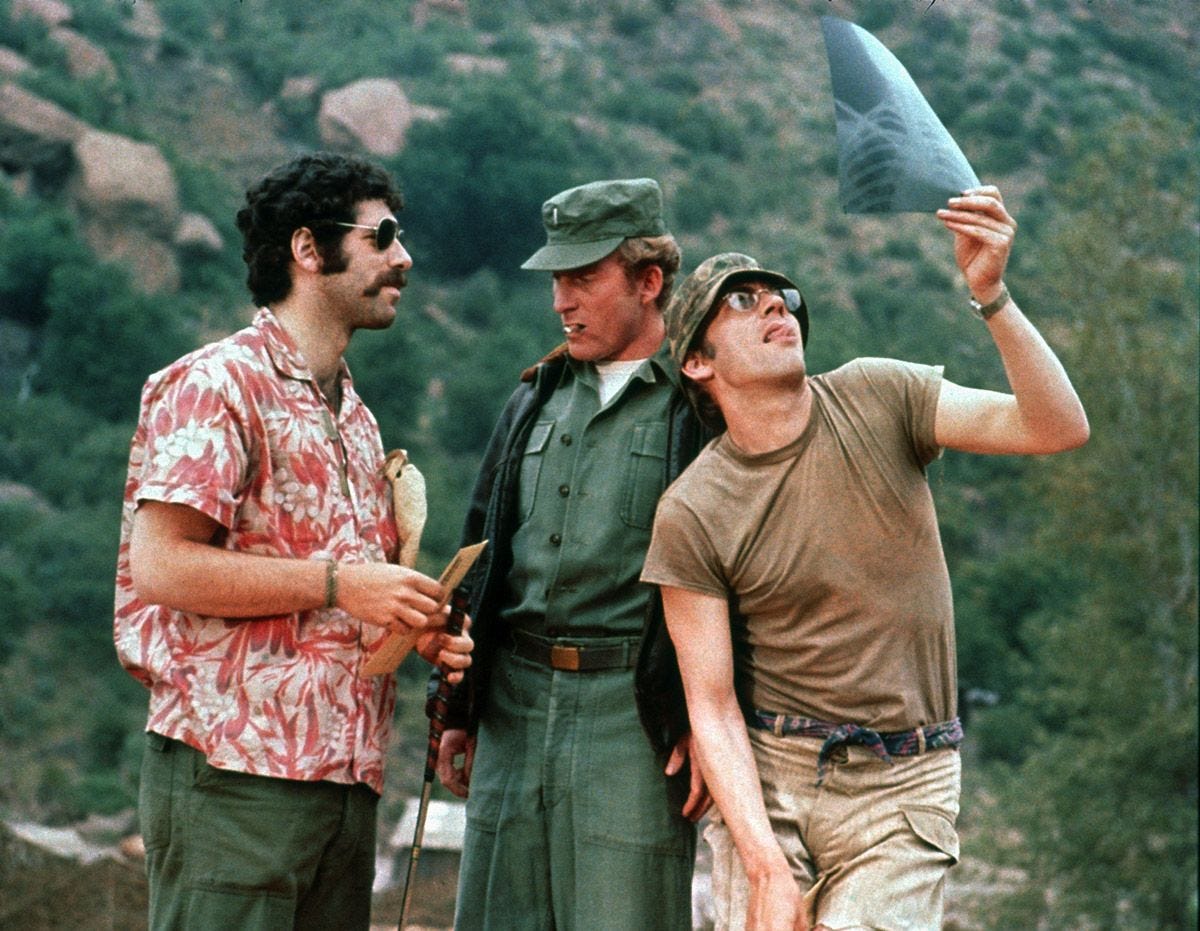

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969): wife swapping Los Angeles comedy featuring E.G. as the straightest laced member of a bourgeois friendship group dabbling with unfree late 60s freedoms. M*A*S*H (1970): cynical buddy comedy set in a military hospital during the Korean War; E.G. at an extreme of furious zaniness. Getting Straight (1970): Vietnam/West Coast campus comedy starring E.G. as a grad student and veteran trying to get teaching qualification and failing to stay out of the protests; the only cinematic depiction I’ve seen of a US grad school oral qualifying exam in English Literature. Move (1970): surrealist New York comedy about E.G. (playing a part-time dog walker and pornography ghostwriter) trying to move apartment while regularly dissociating into a fantasy world. I Love My Wife (1970): cynical adultery comedy, featuring E.G. as a successful surgeon who becomes increasingly dissatisfied with his life and sleeps around out of boredom and hollow ambition. Little Murders (1971): cynical neurotic New York black comedy about the hollowness of contemporary life in a city riddled with meaningless violence, with E.G. as a passive man drifting into deeper futility, redeemed by succumbing to homicidal urges. The Touch (1971): E.G. goes to Sweden to work with Ingmar Bergman on a miserable adultery drama which is also obliquely about generational trauma and the Holocaust; E.G.’s most serious and most explicitly Jewish role, which also maybe led to him having a small breakdown. A couple of years off while he has the breakdown, before returning to do The Long Goodbye (1973): cynical drifting Los Angeles noir deflating the mythology of Humphrey Bogart, with E.G. as an orally fixated wise-acre who sweats his way through a black suit in the blazing sun—easily a career highlight. Busting (1974): cynical/gritty Los Angeles buddy cop movie about the Vice Squad, quite grimly homophobic and hollow; E.G. appears opposite Robert Blake, an actor who would later be murkily involved in killing his wife. Who? (1974): dreary and boring Cold War sci-fi spy thriller; E.G. looks absolutely incensed that he’s been reduced to this and doesn’t put in any effort at all. California Split (1974): cynical and deeply homosocial Los Angeles buddy comedy about the hollowness of gambling addiction, with E.G. opposite George Segal; as with The Long Goodbye (also directed by Robert Altman) E.G. is truly at his best here; one of the very few actually good films from this period in his career.

You can subscribe to Andrew’s excellent film diary here.